In today's world, the debate between those adhering to the principles of a free market and those who've put their hopes in the modern welfare state guides most of the economic policy we see around us. However, just fifty years ago, the ruling paradigm was completely different: advocates of market economies were challenged by countries implementing a high level of state control, which included precise calculations for the production and consumption of goods and services, based on plans designed by state economists, in a period we now know as the Cold War.

This three part series of articles will seek to discuss all forms of economic planning, with the first being dedicated to understanding why the central model has essentially disappeared from public discourse, as understood through the lens of relevant liberalisation reforms. As such, the two largest geopolitical powers that have adopted a centrally-planned system, at a point in their history, were the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. Starting with the Soviet Union, I want to comparatively highlight two important events: the implementation of the New Economic Policy and of the Perestroika, but then move on to China’s development of Dengism.

The NEP (1922) was responsible for the initial transformation of Tsarist Russia’s feudal system into a market-based one, as deemed necessary by Vladimir Lenin. As such, the country managed to reverse most of the economic damages caused by WW1, production levels being restored to those of 1913, but with small-scale industries being owned by entrepreneurs and cooperatives. What followed was the abandonment of this policy, it being replaced by rapid state-controlled industrialization, at an unprecedented pace. Despite said achievements, what remains certain is the numerous shortages experienced by Soviet citizens, leading to famines (as seen in 1932-1933 and 1946-1947), caused by the neglect of sustainable development of infrastructure, through the numerous failures of agricultural collectivization, which was previously tackled successfully by the NEP.

Secondly, the period of “Perestroika” (1980s) was one of urgent reform for the Soviet Union, with Mikhail Gorbachev adopting policies such as allowing state enterprises to determine their own production quotas, the bailout regime for cooperatives was greatly reduced, with the means of production being transferred from the state back to worker collectives - for the first time since the NEP, private ownership was legal and encouraged. Additionally, because of vast cultural liberalisation and the improvement of human freedom, the positive change brought by the Perestroika was not enough to deter political opponents to the Communist Party, which were now freer to act, and as such, the Soviet Union fully dissolved in 1991.

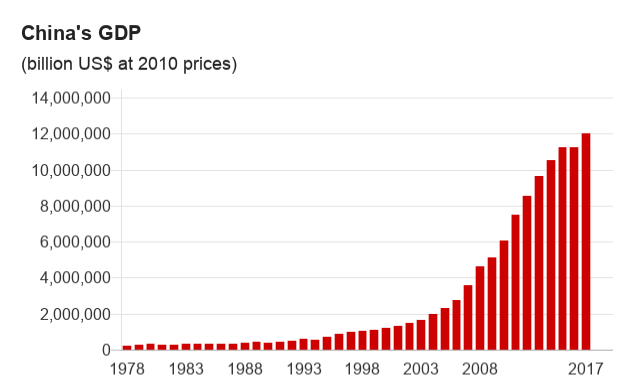

When it comes to the People’s Republic of China, a sustainably positive result was observed in its transition from central planning to a market economy. After Deng Xiaoping’s rise to power in the 1980s, a fundamental reshaping of China was imminent, and as such, the “Chinese economic miracle” was born. Starting with the opening-up of the country for foreign investment, the permission of entrepreneurs to start businesses, but also the de-collectivization of agriculture, what followed was a never-seen-before 50-year economic rise to power, which, today, has put China in the position of a great world power.

While having discussed three instances of market liberalisation leading to improved results for otherwise centrally-planned economies, in the next part of my article we will be addressing proposals for incredibly interesting high-tech solutions, which would seek to fix all previous inefficiencies of said systems (which were usually patched through market means).

Bibliography:

Comentarios